Metro-North Railroad

| Metro-North Railroad | |

|---|---|

|

Metro-North Railroad provides services in the lower Hudson Valley and coastal Connecticut. |

|

| Reporting mark | MNCR (revenue), MNCW(work trains) |

| Locale | Hudson Valley, southwestern Connecticut |

| Dates of operation | 1983–present |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) Standard gauge |

| Headquarters | 347 Madison Ave. New York, NY 10017 |

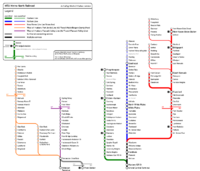

The Metro-North Commuter Railroad (reporting mark MNCR), trading as MTA Metro-North Railroad, or, more commonly, Metro-North, is a suburban commuter rail service that is run and managed by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), an authority of New York State. It is the second busiest commuter railroad in the United States as measured in terms of overall monthly ridership, a position it has held since the fourth quarter of 2001.[1] Metro–North runs service between New York City to its northern suburbs in New York and Connecticut. Trains terminate in places respective to their branch line; these locals include, in New York State, in Port Jervis, Spring Valley, Poughkeepsie, and Wassaic; in Connecticut, in New Canaan, Danbury, Waterbury, and New Haven. Metro-North also provides local rail service within New York City with a reduced fare.

The MTA, which also operates the New York City Transit Authority buses and subways, as well as the Long Island Rail Road, has jurisdiction, through Metro-North, for use of the railroad lines on the western and eastern portion of the Hudson River in New York State. Service on the western side of the Hudson is operated by New Jersey Transit under contract with the MTA. There are 120 stations operated by Metro-North.

Contents |

Lines

East of Hudson

Three Metro-North lines provide passenger service on the east side of the Hudson River, all of which terminate at Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan: the Hudson Line, Harlem Line and New Haven Line. An additional line, the Beacon Line, is used for internal equipment moving between the Brewster shop & Danbury station, and does not provide passenger service.

The Hudson and Harlem Lines terminate in Poughkeepsie and Wassaic, New York, respectively. No other branches extend from these lines.

The New Haven Line is operated through a partnership between Metro-North and the State of Connecticut. Under the arrangement, the Connecticut Department of Transportation (ConnDOT) owns the tracks and stations within Connecticut. ConnDOT also finances and performs capital improvements to such, within Connecticut. MTA owns the tracks and stations, and handles capital improvements for such within New York State. MTA also performs routine maintenance and provides police services for the entire New Haven Line, its branches and stations. New cars and locomotives are typically purchased in a joint agreement between MTA and ConnDOT, with the agencies paying for 33.3% and 66.7% of costs, respectively. ConnDOT pays more because most of the line is in Connecticut.

The New Haven Line has three branches providing connecting service in Connecticut- the New Canaan Branch, Danbury Branch and Waterbury Branch. At New Haven, the Shore Line East connecting service, which is run by Connecticut, continues east to New London.

Freight trains occasionally run on the New Haven Line as CSX, P & W, and Housatonic Railroad each have trackage rights on certain sections.

Amtrak also operates intercity train service along the New Haven and Hudson Lines. Because the New Haven Line is also part of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, high-speed Acela Express trains run on the line from New Rochelle to New Haven Union Station

West of Hudson

Metro-North also provides service on trains west of the Hudson River that originate from Hoboken Terminal, New Jersey. This service is jointly run by Metro-North and New Jersey Transit, under contract. There are two branches of the west-of-Hudson service, the Port Jervis Line, and the Pascack Valley Line. [2] The Port Jervis Line is accessed from two New Jersey Transit lines, the Main Line and the Bergen County Line.

The Port Jervis Line terminates in Port Jervis, New York, and the Pascack Valley line in Spring Valley, New York; these lines are in Orange and Rockland Counties, respectively. Trackage on the Port Jervis Line north of the Suffern Yard is leased from the Norfolk Southern Railway by the MTA. New Jersey Transit, however, owns all of the trackage that is part of the Pascack Valley Line in Rockland County, New York.

Because the majority of the stops for the Main Line and Pascack Valley Line are in New Jersey, New Jersey Transit provides most of the rolling stock, and all the staffing, to operate the service west of the Hudson River, pooled with Metro-North supplied equipment. However, Metro-North equipment has been used on other lines that are operated by New Jersey Transit on the Hoboken division.

All stations west of the Hudson River in New York, except for Suffern, are owned and operated by Metro-North.

History

The New York Central, New Haven, and Erie Lackawanna operations

Before the Metro-North service was running as it is today most of the trackage east of the Hudson River and in New York State, was under the control of the large New York Central Railroad (NYC). The New York Central initially operated three commuter lines, two of which ran directly into Grand Central Terminal. Metro-North's Harlem Line had been initially a combination of trackage from the New York and Harlem Railroad and the old Boston and Albany Railroad, running from Manhattan to Chatham, New York in Columbia County. At Chatham passengers could transfer to long distance trains on the Boston and Albany that would take them to destinations in Albany, Boston, Vermont, and Canada.[3] In the 1870s, the New York & Harlem Railroad was bought by Commodore Vanderbilt, which added the railroad to his complex empire of railroads, which were run by the New York Central. The Boston and Albany would come under ownership of the NYC in 1914.[4]

The NYC also operated its famous four tracked Water Level Route which paralleled the Hudson River, Erie Canal, and Great Lakes on a route from New York to Chicago via Albany. The route was fast and popular due to the lack of any significant grades along the line. The section of the Water Level route between Grand Central and Peekskill, New York, the northern most station in Westchester County became known as the NYC's Hudson Division, which operated frequent commuter service in and out of Manhattan. Stations to the north of Peekskill, such as Poughkeepsie, were considered to be long distance services. The other major commuter line was the Putnam Division running from a terminal station at 155th Street in The Bronx to Brewster, New York. Passengers would transfer to the IRT 9th Avenue Line to reach destinations in Manhattan.

From the mid-1800s until 1969 the New Haven Line, including the New Canaan, Danbury, and Waterbury branches, was owned by New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad (NYNH&H). These branches were started in the 1830s by the as a system of horse-pulled cars, later replaced by steam engines, on a route that that connected the then-early Lower Manhattan to Harlem. Additional lines started in the early nineteenth century included the New York and New Haven Railroad and the Hartford and New Haven Railroad, which provided routes to Hartford, Springfield, Massachusetts, and eventually Boston. The two roads would merge to become the New York, New Haven, and Hartford in 1872 growing into the largest passenger and commuter carrier in New England. In the early 1900s the New Haven came under the control of the wealthy J.P. Morgan. Morgan's bankroll allowed the NYNH&H to modernize by upgrading stream power with both electric (along the New Haven Line) and diesel power (branches and lines to eastern and northern New England). The company saw much profitability throughout the 1910s and 20's until the Great Depression of the 30's would force the company into bankruptcy.[5]

Commuter services west of the Hudson River, which make up today's Port Jervis and Pascack Valley lines, were initially part of the Erie Railroad. The Port Jervis Line, built in the 1850s and 60's, was originally part of the Erie's mainline from Jersey City to Buffalo, New York. The Pascack Valley Line was built by the New Jersey and New York Railroad, which became a subsidiary of the Erie. Trains that service Port Jervis fomerly continued all the way to Binghamton and Buffalo, New York (but today is only used by freight trains), while Pascack Valley service continued to Haverstraw, New York. In 1956 the Erie Railroad began a somewhat successful merger with its rival the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, and in 1960 they formed the Erie Lackawanna which became responsible for the services. The services were re-routed to the Lackawanna's Hoboken Terminal at this time.

Penn Central

Passenger rail, both long distance and commuter, began to falter after World War II. By the 1950s the railroad industry as a whole would begin to experience a significant downturn due to overregulation, market saturation, and competition from the car, and the airplane. Commuter lines would take a significant hit from this downfall.

Commuter services, historically had always been money losers, and were usually subsidized by the money generated by long distance passenger and freight services. However, as these profits disappeared, commuter services usually were the first to be affected. Many railroads began to gradually discontinue their commuter lines after the war. By 1958, the New York Central had already suspended service on its Putnam Division, while the newly formed Erie Lackawanna, in an effort to make a successful merger, began to prune some of its commuter services. However, as a whole, most New Yorkers still chose the train as their primary means of commuting making many of the other lines heavily patronized. Thus the New York Central, the New Haven, and the Erie Lackawanna had to maintain some level of service on these lines. Corporate mergers between railroads was seen as a way to curtail these issues by combining capital, services, and creating efficiencies. In 1968, following the Erie Lackawanna's example, the New York Central and its rival the Pennsylvania Railroad formed Penn Central Transportation with the hope of revitalizing their fortunes. In 1969 the now bankrupt New Haven was also combined into Penn Central by the Interstate Commerce Commission. However, this merger eventually failed, due to large financial costs, government regulations, corporate rivalries, and lack of a formal merger plan. In 1970 Penn Central declared bankruptcy, at the time being the largest corporate bankruptcy ever declared.

In 1972, the now bankrupt Penn Central petitioned the ICC to allow for the discontinuance of its commuter services. Penn Central's long distance passenger services had been taken over by the newly formed, government owned, Amtrak a year earlier and thus subsidies for the continuance of the New York area lines would have to come from the states of New York and Connecticut. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, an agency formed by New York State in 1965 with the purpose of subsidizing the New York City Subway and the Long Island Rail Road, decided to provide the funds for these lines with Penn Central operating them. The state of Connecticut also provided subsidies in an operating agreement they made with the MTA.

Conrail

Many of the other Northeastern railroads at the time, including the Erie Lackawanna, were following Penn Central into bankruptcy and so the federal government decided to fold these lines into the newly created Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) in 1976. Conrail was initially given the responsibility of operating the former commuter services of these fallen railroads including the Erie Lackawanna's and Penn Central's.

MTA operation and the formation of Metro-North

However, Conrail was being floated by the federal government as a private for profit freight only carrier. Even with state subsidies, Conrail did not want the responsibility of taking on the operating costs of the money losing commuter lines, an act they officially were relieved from by the passage of the Northeast Rail Act of 1981. Thus, it became essential that state owned agencies both operate and subsidize their commuter services. Over the next few years commuter lines under the control of Conrail were gradually taken over by state agencies such as the newly formed New Jersey Transit in New Jersey, and the established SEPTA in southeastern Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority in Boston. The MTA in conjuncture with the Connecticut Department of Transportation formed the Metro-North Commuter Railroad in 1983.

Metro-North also took the responsibility of operating the former Erie Lackawanna services west of the Hudson and north of the New Jersey state line. However, since those lines are physically connected to New Jersey Transit lines, their operations were contracted to NJ Transit, with Metro-North subsidizing the service and supplying equipment.

Much work was needed in reorganization, as significant business success would not appear for at least two decades, following the altogether faltering railroad industry in the 1970s.[3] Conrail and later Metro-North had decided to trim whatever services they felt were unnecessary. A significant portion of the old NYC Harlem Line between Millerton and Chatham, New York was completely abandoned by Conrail leaving residents in Dutchess and Columbia Counties with no other means of public transportation. Nonetheless, most of the old commuter lines were kept in service, however, they were in much need of a repair.

The first major project undertaken by the new agency was the extension of the third rail electrification on the Harlem line from North White Plains to a new station at Brewster North (since renamed Southeast). This was completed in 1984. In the early 1990s all wayside signals that did not protect switches and interlockings north of Grand Central Terminal were removed and replaced by modern cab signaling.

Metro-North spent the better part of its early days updating and repairing its infrastructure. Stations, track, and rolling stock all needed to be repaired, renovated, or replaced. Nonetheless, the railroad succeeded and by the mid nineties gained both respect and monetary success, according to the MTA's own website. 2006 was the best year for the line, as there was a 97.8% rate of on-time trains, a record amount of ridership (76.9 million people), and a passenger satisfaction rating of 92%.[3]

The Harlem and Hudson lines, and the Park Avenue mainline to Grand Central, are now owned by Midtown TDR Ventures LLC, who bought them from the corporate successors to Penn Central, [6] but the MTA has a lease on the entire system extending to 2274, and an option to buy starting in 2017.[7]

Plans

Metro-North is continually upgrading trackage and station facilities.[8]

Metro-North is also in the process of upgrading its Operations Control Center in Grand Central Terminal. In 2008, construction began on a new Operations Control Center to replace all control hardware. Software upgrades are providing for state of the art rail traffic technology. Construction is underway on the OCC at GCT and construction on a backup OCC is also underway.

East of Hudson

Hudson Line

No further plans are in the works on the Hudson Line at this time. On May 23, 2009 a new station opened, Yankees-E. 153rd Street, which is accessible from all three Metro-North Railroad, East of Hudson lines with direct game day trains. The trains to the new station that originate from the New Haven and Harlem lines gain access to the Hudson line station via the wye at Mott Haven Junction. This marks the first time in the long history of these lines that revenue service operates across this section of the wye.

Northward expansion of the Hudson Line has often met opposition from residents of communities including Hyde Park and Rhinecliff, even though the latter is home to Amtrak's Rhinecliff-Kingston station, frequented by commuters who live in northern Dutchess and Ulster Counties.[9]

Harlem Line

There are plans to redevelop the former Wingdale Psychiatric Center into a mixed-use commercial and residential neighborhood known as Dover Knolls, centered around the Harlem Valley-Wingdale Station.

The northward expansion of the Harlem Line took place most recently when it was expanded from Dover Plains to Wassaic in 2001, requiring a costly rebuilding of tracks that were abandoned years before. Going even further north would require further substantial investment to rebuild tracks; grade crossings, stations and other facilities which existed in the past but were removed long ago, as well as obtaining eminent domain for the current train property used by the Harlem Valley Rail Trail. However, expansion of either line would be limited to Dutchess County. Extending Metro-North service into Columbia County would require changes to the MTA charter, and residents of that county would become subject to the MTA tax, therefore extending the Harlem Line back up to Chatham would be unlikely.

New Haven Line

Discussions are underway to re-electrify the Danbury Branch[10] with a concurrent expansion to New Milford. Work began in late 2007 on a third Metro-North station for the Town of Fairfield, Connecticut. This station, in eastern Fairfield near the Bridgeport line, was to be part of a large mixed-use development known as Fairfield Metro Center. Many of the developers have backed out of the project due to the recent economic crisis, but the station is still being built. Connecticut officials and Metro-North are conducting environmental studies for a new station in West Haven. ConnDOT is also moving forward on a study to increase freight service on the New Haven Line in an effort to reduce the number of trucks on the congested Connecticut Turnpike. A number of projects are either planned or underway that will upgrade the catenary system, replace outdated bridges, and straighten certain sections of the New Haven Line to accommodate the Acela's 240 km/h (150 mph) maximum operating speeds. [11] Much of the catenary system has not been upgraded since the New Haven Railroad installed the catenary wires in 1907. The Danbury Branch is going to receive $30 million for upgrades of stations along the line and also implementation of a new signal system.

Plans to extend the Waterbury Branch northeast from its current terminus in Waterbury are currently under discussion. The extension would bring passenger rail service to central Connecticut, including the two largest cities in Connecticut without passenger rail service, Bristol and New Britain, and on to Hartford, where transfers to Amtrak would be possible.

West of Hudson

The MTA is working with the Tappan Zee Bridge Environmental Review on several options where a future replacement for the Tappan Zee Bridge would include a rail line to connect the Port Jervis Line in Rockland County to the Hudson Line in Westchester County. "Alternatives 4A, 4B and 4C" all include plans for such a rail line to connect with the Hudson Line at Tarrytown, providing a one-seat ride from Rockland County to Grand Central Terminal in New York City. All three also include mass-transit service across Westchester County, connecting to the Harlem Line in White Plains, and the New Haven Line at Port Chester. The only difference between the three is whether the cross-Westchester trip will be accomplished by heavy rail, light rail or rapid bus service.[12]

Metro-North is also considering extending Port Jervis Line service to Stewart International Airport in Newburgh,[13] a move that could make a Tappan Zee Bridge rail line even more useful, as it would serve both commuters and travelers who choose to fly to and from Stewart, instead of the three major New York City-area airports.

Access to Penn Station

In September 2009 Metro North announced plans for a $1.7 million Environmental Impact Statement on accessing Penn Station. Metro North has been considering the possibility for several decades but never pursued it because no space was available at Penn Station.[14]

The project depends upon the success of the East Side Access which would reroute some Long Island Rail Road trains from Penn Station to Grand Central and the Mass Transit Tunnel which reroute some New Jersey Transit trains from Penn Station to a depot under 34th Street. Those two projects are scheduled for completion in 2014 and 2017 respectively at the earliest.[14]

New Haven Line trains would enter the Hell Gate Line through New Rochelle. At the Sunnyside Yards they would enter Manhattan via the East River Tunnels. Stations would be built at Co-Op City, Parkchester and Hunts Point.[14]

Hudson Line trains would access Penn Station via a change at Spuyten Duyvil and would travel under Riverside Park via Amtrak's Empire Connection. Plans call for new stations on West 125th Street[15] and West 62nd Street in Manhattan (the site of the historic New York Central West 60th Yards which is now part of the Trump Place development) .[16]

Technical details

East of Hudson

Most services running directly into Grand Central Terminal are electric powered.

In the case when the diesel powered train runs into Grand Central, General Electric GENESIS P32 electro-diesel locomotives capable of switching to a pure electric mode using contact shoes to contact the railroad's under-running third rail power distribution system. Shoreliner series coaches are used in push-pull operation.

On the Hudson Line, local trains between Grand Central and Croton-Harmon are powered by electrified third rail. Through trains to Poughkeepsie are diesel powered and do not require a change of trains at Croton-Harmon. The Harlem Line has third rail from Grand Central Terminal to Southeast and are powered by diesel north of that station to Wassaic. At most times, passengers traveling between Southeast and Wassaic must change trains at Southeast to a diesel-powered train. These trains are powered by Brookville BL20-GH locomotives. Electric service on the Hudson and Harlem lines is provided using the M1, M3, and M7 MU cars.

The New Haven Line is unique in that trains are powered through both 700 V DC from a third rail or 13.8 kV AC from an overhead catenary wire. The line from approximately Woodlawn to Pelham (3 miles, or 4.8 km), is powered by third rail, while from Pelham, New York east to New Haven Union Station (58 miles, or 93 km) is powered by catenary. M2, M4 and M6 railcars are used. New M8 railcars, slated to replace the older M2s, are on order.

The New Canaan Branch also uses catenary. The Danbury Branch was formerly electrified but in 1961 became a diesel-only line. The Waterbury Branch, the only east-of-Hudson Metro-North service which has no direct service of any sort into Grand Central, is diesel-only.

The third rails on the three Metro-North lines which go into Grand Central Terminal are unusual in that power is collected from below the third rail as opposed to above, unlike most other third rail systems (including the Long Island Rail Road and New York City Subway). This system is known as the Wilgus-Sprague third rail and the SEPTA Market-Frankford Line in Philadelphia and Metro-North are the only two electric rail systems in North America that use it. This allows the third rail to be completely insulated from above, thus decreasing the chances of a person being electrocuted by coming in contact with the rail. It also reduces the impact of icing conditions on operations during winter weather.[17]

West of Hudson

Most of the rolling stock on west-of-Hudson Metro-North lines consists of Metro-North owned and marked Comet V cars, although occasionally other NJT cars are used, as the two railroads pool equipment. The trains are also usually handled by EMD GP40FH-2, GP40PH-2, F40PH-2CAT or Alstom PL42AC diesel locomotives, although any Metro-North or New Jersey Transit diesel can show up.

Reporting marks

Although Metro-North uses many abbreviations (MNCR, MNR, MN, etc.) there are two official reporting marks used on equipment. For non-revenue equipment, the mark registered and recognized on AEI scanner tags is 'MNCW', while revenue equipment is identified using 'MNCR'.

Active rolling stock

Includes passenger revenue equipment only.

| Builder and model | Photo | Built | Power | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locomotives | ||||||

| GE P32AC-DM |

1992–1994 | 3200 hp | Dual mode for operation into Grand Central Terminal | |||

| Brookville BL20-GH |

|

2008–2009 | 2250 hp | Used on branch line shuttles, cannot enter Grand Central Terminal | ||

| Electric Multiple Units | ||||||

| Budd M2 |

|

1972–1977 | 650V DC Third Rail under running 12.5kV 60Hz AC catenary |

220 out of 244 remain in service, being replaced by M8s | ||

| M3A |  |

1984–1985 | 650V DC Third Rail under running | Will undergo CSR after the M8s have arrived | ||

| Tokyu Car M4 |

1987–1988 | 650V DC Third Rail under running 12.5kV 60Hz AC catenary |

3 car sets | |||

| Morrison Knudsen M6 |

1993 | 650V DC Third Rail under running 12.5kV 60Hz catenary |

3 car sets | |||

| Bombardier M7A |

2002 | 650V DC Third Rail under running | Replaced M1s | |||

| Kawasaki M8 |

2009– | 650V DC Third Rail under running 650V DC Third Rail over running 12.5kV 60Hz AC catenary 25kV 60Hz AC catenary |

Delivery ongoing. Will be able to operate on Shore Line East and may eventually operate into Penn Station. | |||

| Push Pull Coaches | ||||||

| Bombardier Shoreliner I |

1983 | Non-powered | One door on each end, odd # trailers have toilets | |||

| Bombardier Shoreliner II |

1987 | Non-powered | Near identical to Shoreliner Is | |||

| Bombardier Shoreliner III |

1991 | Non-powered | Have center doors in addition to end doors, odd # trailers have toilets | |||

| Bombardier Shoreliner IV |

1996–1998 | Non-powered | Engineers side door removed in cab cars, odd # trailers have toilets | |||

| Alstom Comet V |

|

2006 | Non-powered | Operated by NJ Transit for west-of-Hudson service | ||

Fare policies

Metro-North offers many different ticket types and prices depending on the frequency of travel and distance of the ride. While the fare policies of the "East of Hudson" and "West of Hudson" divisions are essentially the same, they operate differently because the West of Hudson trains are operated by New Jersey Transit therefore using their ticketing system.

East of Hudson

Tickets may be bought from a ticket office at stations, ticket vending machines (TVMs), online through the "WebTicket" program, or on the train itself. Monthly tickets may also be bought through the MTA's "Mail&Ride" program where monthly passes that are paid in advance, usually by credit card, are delivered by mail to the rider. There is a discount for buying tickets online and through Mail&Ride. A surcharge is added on top of the standard price if a ticket is purchased on a train.

Ticket types available include One-Way, Round-trip (two one-way tickets), 10-trip, Weekly (unlimited travel for one calendar week), Monthly (unlimited travel for one calendar month), and special student and disabled fare tickets. MetroCards are also available on the reverse side of the weekly, monthly, and round-trip tickets.

All tickets to/from Manhattan (Grand Central Terminal and Harlem-125th Street) are distinguished as being peak or off-peak. Peak fares, which are substantially higher than off-peak trains, apply to trains that arrive in Grand Central between 5 AM and 10 AM and trains that leave Grand Central between 5:30 AM and 9 AM and from 4 PM to 8 PM all coinciding with the standard New York City rush hours. Trains arriving at Grand Central during the PM peak hours are not subject to peak fare. Off-peak fares are charged all other times including weekends and holidays. Tickets for travel outside of Manhattan are called "intermediate" tickets and the peak/off-peak rules do not apply.

The fares themselves are distinguished by the 14 zones that the lines are divided into within New York State. In Connecticut, the fare structure is more complex due to the many branches on the New Haven line. Generally, these zones correspond to express stops on the lines and from "blocks" of service within the schedules.

West of Hudson

The fare structure resembles the New Jersey Transit fare structure, and less like that of east-of-Hudson trains.

Community relations

Mascot

Metro-North sponsors a mascot named Metro-Man, a small remote-operated robot that "speaks" about rail safety during appearances at schools and other events.

Croton-Harmon Shop Open House

Each October, one Saturday is set aside for the railroad to hold an open house at the Croton-Harmon heavy repair facility located next to the station. An extensive tour of the facility is given showing all facets of repair and maintenance along with detailed exhibits that display the different parts of the system such as power and signaling. Also a large display of the many diesel locomotives is set up and a free "Fall Foliage" ride is offered from the shop north to the interlocking south of Garrison station and back. In addition, the Metro-North Police have a display of their equipment and the K-9 dog corps put on a show so the visitors can see how highly skilled dogs can sniff out contraband and explosives. No open house was held in 2009 due to construction at the shop.

In popular culture

The railroad has been featured in several films, including U.S. Marshals, Steven Spielberg's War of the Worlds, and The Ice Storm. The trains are also mentioned in the movie Madagascar as the rail service that Marty the Zebra wanted to use to get to Connecticut. Hudson Line trains were also the setting for the 1984 film Falling in Love starring Robert De Niro and Meryl Streep. The film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind was filmed on a Metro-North train representing the Long Island Rail Road.

Recent Tuscan Dairy Farms and Verizon Fios commercials featured Crestwood on the Harlem Line.[18]

See also

- Long Island Rail Road

- List of Metro-North Railroad stations

- Transportation in New York City

- Transportation in New York State

- CityTicket

References

- ↑ Per American Public Transportation Association quarterly ridership reports, available here: http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Pages/RidershipArchives.aspx

- ↑ http://mta.info/mnr/html/mnrmap.htm Metro-North map

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Railhistory

- ↑ MTA Metro-North Railroad

- ↑ http://www.nhrhta.org/htdocs/history.htm

- ↑ Notice Of Exemption: 12/07/2006 - FD_34953_0

- ↑ Weiss, Lois (2007-07-06). "Air Rights Make Deals Fly". New York Post. http://www.nypost.com/p/news/business/item_cAK3GRQ1DUIqiufcu5cheO. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ↑ "MTA Service Updates". http://www.mta.info/mnr/html/serviceupdates.htm.

- ↑ C. J. Chivers (1999-10-12). "Hudson Towns Wary of Rail's Reach; Commuter Line Extension Faces Hostility in Bucolic North Dutchess". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9400E4D91730F931A25753C1A96F958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ "Danbury Branch Electrification Feasibility Study". http://www.danburybranchstudy.com/. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ http://www.mta.info/mnr/html/mileposts.pdf (Reference unavailable at this website

- ↑ Tappan Zee Bridge Environmental Review

- ↑ Trans-Hudson study

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Cassidy, Martin B. (2009-09-08). "Metro-North reviving Penn Station-New Haven Line plans". Connecticut Post. http://www.ctpost.com/default/article/Metro-North-reviving-Penn-Station-New-Haven-Line-31067.php. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ↑ Namako, Tom (2009-09-09). "Next Stop: Penn Sta.". New York Post. http://www.nypost.com/p/news/regional/manhattan/next_stop_penn_sta_spyMzFHiYkM2gqrEWKXNlI. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ↑ METRO-NORTH CONSIDERS W. 60s STOP - West Side Spirit - March 26, 2009

- ↑ Middleton, William D. (2002-09-04). "Railroad Standardization - Notes on Third Rail Electrification". Railway & Locomotive Historical Society Newsletter 27 (4): 10–11. http://rlhs.org/rlhsnews/pdfs/nl27-4.pdf. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ↑ Tuscan Dairy Farms Commercial

External links

- Metro-North map

- MTA Metro-North Railroad

- New Jersey Transit (West of Hudson lines ONLY)

- Connecticut Rail Commuter Council, "a consumer liaison between riders and the Connecticut Dept. of Transportation (CDOT), Metro-North, and Shore Line East railroads"

- The history of The New York Central Railroad in the Region

- MTA Arts for Transit-The Official NYC Subway Art and Rail Art Guide

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | Now |

| M1 (LIRR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M3 (LIRR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C3 (LIRR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M7 (LIRR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M1A (MNCR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M2 (MNCR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M3A (MNCR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M4 (MNCR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M6 (MNCR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M7A (MNCR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M8 (MNCR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||